- Home

- Georgia Pellegrini

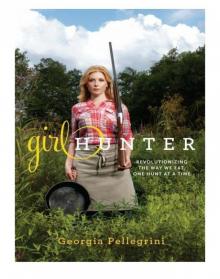

Girl Hunter

Girl Hunter Read online

Table of Contents

ALSO BY GEORGIA PELLEGRINI

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

The Beginning

Chapter 1 - The Beginning and the End

Wild Turkey Schnitzel

Wild Turkey and Oyster Stew

Whiskey-Glazed Turkey Breast

Swedish Turkey Meatballs

Chapter 2 - The Village

Beer-Battered Fried Dove Breast

Poached Dove and Pears in Brandy Sauce

14-Dove Putach

Chapter 3 - Hunting the Big Quiet

Braised Javelina Haunch

Adobo Javelina Backstrap

Javelina Chili

Pulled Javelina

Chapter 4 - Grouse and Other Creatures

Partridge with Pancetta in Orange Brandy Sauce

Whole Pheasant Poached in Juniper Sauce

Apple Wood–Smoked Pheasant

Grouse with Cabbage and Chestnuts

Chapter 5 - Calamity Jane

Elk Jerky

Elk-Stuffed Cabbage Rolls

Corned Elk

Moroccan Elk Stew

Chapter 6 - The Upland High Life

Braised Pheasant Legs with Cabbage and Grapes

Chukar Pie

Quail en Papillote

Quail Kebabs

Stuffed Quail

Chapter 7 - A Moveable Hunt

Curried Pigeon

Browned Woodcock with Sherry Sauce

Duck with Cherry Sauce

Pheasant with Roasted Apples

Pheasant Tagine

Chapter 8 - Waiting for Pâté in the Floatant

Apple Roast Gadwall

Duck Cassoulet

Coot Legs in Sherry

Duck, Coot, or Goose Confit

Duck Terrine

Goose or Duck Prosciutto

Chapter 9 - All of the Jewels That Go Unnoticed in the World

Braised Venison Shoulder

Liver Mousse

Pan-Seared Deer Liver

Balsamic Deer Heart

Fireplace Venison Tenderloin

Fried Venison Backstrap

Venison Sausage

Smoked Venison Kielbasa

Axis Venison Loaf

Chapter 10 - NASCAR Hog Hunting

Boar Loin in Sherry Marinade

Braised Hog Belly

Cotechino Sausage

Chorizo Sausage

Hog Backstrap, Chops, or Tenderloin

Smoked Whole Hog

Sweet Porchetta Sausage

Hog Croquettes

Hog Ragout

How to Render Fat

Apple Juice Smoked Ribs

Chapter 11 - Seeing the Forest for the Squirrel

Squirrel Brunswick Stew with Acorns

Squirrel Dumplings

Traditional Squirrel Putach

Buttermilk Fried Rabbit

Jugged Hare

Braised Rabbit with Olives and Preserved Lemon

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Gravy

METRIC CONVERSION CHART

Recipe Index

Copyright Page

ALSO BY GEORGIA PELLEGRINI

Food Heroes: 16 Culinary Artisans Preserving Tradition

For T. Kristian Russell

Without you, there would be none of this.

So long as there is lead in the air, there is hope.

—THEODORE ROOSEVELT

Prologue

“Oh my Lord, oh my Lord,” Hollis whispers.

In the next field we can barely make out a set of dark crimson tail feathers moving through the high grass. We move quickly toward the wild turkey, along the levee with our backs bent low, in single file, three of us: a farmer named George Hollis, a man they call “the Commish,” and me. We are an odd group, me half their size, trying to keep up in too-large-for-me, full army camouflage that I borrowed from my brother’s closet—remnants from the days he played paintball with his adolescent friends. The others are in proper hunter’s camouflage with 12-gauge shotguns slung over their shoulders, a couple of plastic turkey decoys dangling from their backpacks, turkey callers clenched between their teeth. They climb up the hill beside the field; I stumble after them in the oversize rubber boots that they bestowed upon me to save me from the snakes. We sit panting behind a tree trunk while Hollis unwraps a piece of camouflage fabric attached to plastic stakes and positions it in front of us as a blind. We wait.

“Okay,” the Commish says. “This bird’s gonna get to meet Miss Georgia. He’s gonna have Georgia on his mind . . . ”

You may be wondering how I ended up here. It was a series of serendipitous introductions, really, a divine aligning of the stars that introduced me to a man named Roger Mancini, a larger-than-life entrepreneur from the Arkansas side of the Mississippi Delta. I had cooked for him from time to time in Nashville, where we have mutual friends, and always found myself reaching deep into my bag of four-star tricks to impress a man so worldly, yet so distinctly a product of the American South.

During one of those dinners, as I glazed a series of Roger’s freshly hunted wild duck breasts with orange gastrique, he overheard me telling a friend that I wanted to hunt. “Hold on now, Georgia,” he said as he sauntered over with a wide-eyed, soulful look, a cigar pressed between his thumb and forefinger, which he pointed at me now, saying, “I’ve got just the man to teach you. My first cousin; we call him ‘the Commish.’”

Roger went on to explain that “the Commish” takes his nickname from the governor-appointed position he has held for many years: commissioner of fish and game for the State of Arkansas, and that he would be honored to introduce me; and then, in the same breath, he moved past me, intent on finding three perfect tomatoes for the Panzenella Salad he had been talking about for some time. It was then that his wife, Betsy, leaned over to me, a glass of Bollinger balanced in her left hand, and said conspiratorially, “Down there, the Commish is a bigger deal than the president of the United States.”

Many months later in early spring, I was introduced to the Commish at an Arkansas hunting camp, the night before a turkey hunt. He was sitting on a tree stump, holding a large Styrofoam cup filled with ice and whiskey in one hand, and cradling a thick cigar in the other, staring into the fire with a serious expression.

He looked up as they introduced me to him, paused, then offered me a drink and a seat by the fire. He had silver hair and his face bore the faint traces of his Lebanese ancestors who had first inhabited this place a century ago.

“You ever shot a gun?” he asked, still staring into the fire, his voice settling onto his words like molasses.

“Um, no, not really,” I said, glancing sideways, feeling the other men at the camp peering at me curiously.

“This twenty-gauge should work pretty well,” he said, opening the shotgun leaning against his chair to look down the barrel. “My daughter Ashley learned on a four-ten because it doesn’t kick, but it’s hard to kill anything with it. The first thing you gotta decide, do you want an automatic or an over an’ under, which is a double barrel—the classic hunting bird gun. Quail hunters, they all shoot over an’ unders, that’s just kinda the old European influence. For you I would use a twenty-gauge. It’s a good turkey gun if you can get ’em close.”

“Okay, that sounds good,” I say, wanting to fit in as much as possible but clearly failing simply by the way I looked in my button-down shirt and J.Crew blue jeans.

We didn’t talk much after that. We just sat there and sipped from our Styrofoam cups and chewed on the crushed ice.

“I’ll pick you up at five tomorrow morning,” he said as I finally got up to leave.

Then he paused and gave me a sober lo

ok from his dark eyes through tinted spectacles.

“Are you sure ’bout this?” he asked.

“Yes, I’m sure,” I said, my voice unrecognizably high pitched.

“A’ right then. I’ll see you tomorrow,” he said.

Now through the turkey caller set between his tongue and the roof of his mouth, just twelve hours later, George Hollis lets out the cluck of a female turkey. The male gobbles back from the brush across the field. George calls again and the old turkey calls back again.

“He’s responding well,” I whisper.

“You know what you’re supposed to say?” the Commish asks.

“What?” I ask.

“He’s gobblin’ his ass off.”

Hollis chuckles.

“You’re hanging out with a bunch of old men now; you gotta remember that,” the Commish says.

As he speaks, a thin red and black head appears through the clearing on the opposite side of the field. I put my head down into the barrel of the gun and look through the scope to get a better look.

“It’s such a little head they have, though,” I say, my voice shaking. “How am I supposed to hit it?”

“You don’t have to get it exactly on him. You just get it close and the spread of the shell pellets will do the rest,” the Commish says.

I feel my hand tighten as the old turkey begins to strut toward the plastic decoys that Hollis has dropped onto the field. The bird has begun his mating march—stepping forward regally with his wings behind him, displaying the purple and green shimmering colors of his tail feathers, his red wattle and long, wiry beard swaying to and fro. He keeps coming forward, step by adrenaline-inducing step, but then instead of going toward the decoys to my left, he suddenly moves right.

“Hold on,” the Commish says. “Just hold on a second.” I obey, my head and heart pounding in unison.

“Get your head down on the gun,” he continues. “Can you see the red dot on the end of your shotgun?”

“Yeah,” I reply. But I can’t see the turkey. “What happens if I miss the first shot?” I whisper, trying to veil my rising panic.

“Don’t worry about it,” the Commish says, guiding my gun as I look through the scope like a blind man in a maze, with no idea of what is beyond the camo blind or where the ol’ gobbler is doing his dance. I see nothing but the makeshift fence, the cluster of trees and the field, and beyond that the Mississippi, the color of mercury, moving languidly in the distance.

There is a moment of stillness and utter silence when the world seems to be on mute, and then suddenly, hardly 10 yards away, the turkey appears in my scope, so close he is almost in my face. I let out a gasp.

“Do you see him? Do you see him?” the Commish whispers, showing the first signs of real emotion since I’ve met him.

I lean forward and look down the rib of the shotgun toward the red dot at the tip of the barrel, and position it on the head of the bird only a few yards away, my hands shaking, my heart feeling almost certainly too large to fit in my chest. I wait for my breath to become at least a bit more steady, I squint, and then I slap the trigger. The sound echoes through the woods and the field below us and I feel a thrust into my right shoulder as the gun kicks back. The ol’ gobbler jumps into the air, in a moment of confusion, levitates higher, toward the trees, and then finally . . . out of sight.

I look at the Commish and feel my cheeks turn hot.

Hollis jumps out of his seat and howls, “Is that a turkey hunt or what?!” as I sink my head down further in embarrassment.

“What did he do there, Georgia?” the Commish asks, grinning.

“He gobbled his ass off,” I say, suppressing a smile. Hollis howls with laughter.

“That ‘responding well’ works in upstate New York, but down here it doesn’t. We’re not letting you go back to be a Yankee; you’re from the South now, Baby. Anyone who can put on camo and go hunting with a bunch of rednecks is my kind of girl.”

It was at that moment, my cheeks burning with a strange new cocktail of shame and exhilaration, a feeling of determination rising slowly in my chest, that I knew I had just been indoctrinated into a brave new world.

Little did I know, this was just the beginning.

Civilized life has altogether grown too tame, and, if it is to be stable, it must provide harmless outlets for the impulses which our remote ancestors satisfied in hunting.

—BERTRAND RUSSELL

The Beginning

Watching the orange bobbin float by under the willow tree was a kind of pleasure I didn’t know existed until it stopped. Feeling the soil slip under my nails was, too—especially when it ended with a fat worm between my fingers. The bobbin bounced just so over the tiny rivulets of the creek, beneath my feet dangling from my regular boulder. I can still recall the pangs of glee I felt as a six-year-old when the trout pulled on that orange bobbin, and the tug-of-war we played as I pulled on the line and the trout’s brassy color began to reflect the light. The fish pulled my rod down in a sharp arc and its white belly flopped and its dots sparkled and shined and my father’s hands came down to help me reel it in.

I foraged, too, inspecting mushroom guidebooks with scholarly interest; and I painted, using only wild berries and crushed grass as my ink. I hung from vines until they fell and then made vine wreathes that I studded with dandelions and rosehips. I shoveled chicken manure and collected eggs, and made dolls from dried cornhusks. I made jams, as taught to me by an old woman who lived on the bank of the Hudson River, and soon declared myself the Wild Raspberry Queen. I pickled green tomatoes and climbed apple trees to get the very finest fruit. I learned the names of plants with my great-hunched-over-aunt as my guide—and helped her protect her budding flowers from an overabundance of marauding midnight deer—on the land we called Tulipwood.

My mother, on the other hand, was the perennial standard bearer of animal welfare. She was known to bring road-kill deer home in the trunk of her car to give them a proper burial, and to nurse in her home office ailing chickens from our coop. It wasn’t uncommon to trip over a diaper-clad bird named Lorenzo on my way to the kitchen.

During grade school I often visited the Fairy stream and sat on Indian rock. I collected salamanders and slipped them into my pockets for no reason other than their fluorescent green bodies enchanted me.

I preferred not to wear shoes. Or if I had to, then I preferred not to wear anything but shoes. Sometimes I’d sit outside and play the cello in the grass, with just shoes on.

Once, I made the mistake of saying that school was too easy, which prompted a trip from Tulipwood in the Hudson Valley to Manhattan, which prompted a uniform fitting, which prompted early-morning commutes to a rigorous girl’s school in the city. Soon I was penning history notes next to Ivanka Trump by day and shoveling chicken manure by night.

Suddenly I was hopping back and forth between two worlds, divided only by the George Washington Bridge and sizeable trust funds. Suddenly I was spending time with kids during the week who had drivers in sleek black town cars, and on the weekend I was riding along in my dad’s old black stick-shift pickup to get horse manure from the dump.

The seams of my home life began to unravel as I got older. I moved farther away from manure and raspberry jam on the quest for prestigious degrees and prestigious jobs, which were the logical next step after Manhattan prep school. They took over: the heavy books, the ivy walls, the promises of success and fulfilled potential; and I took the path of least resistance into a corporate life. It was a life that nourished my bank account but never my soul, and I found myself looking up one day, while on the trading floor of Lehman Brothers, and saying, “This can’t be the answer.” I wanted to smell fresh air again, to feel the dirt in my fingernails, to collect eggs and stir ruby-colored jam in a pot and watch it grow thick. And so I left, with the taste of hope in my mouth and soon-to-be worthless stock options in my bank account, determined to nourish my soul again.

Two years later I found myself only miles from Wall Str

eet, but a world away, working at an award-winning farm-to-table restaurant on a Rockefeller estate. I had just graduated from the French Culinary Institute and had given up my apartment on Sutton Place in favor of a rented solitary room in Westchester, with no hot water. I had left behind the trappings of the city—the cars and bars and boys—and traded in my laptop for a set of good knives.

The funny thing was that I was working the same hours that I had as a financial analyst, but I was now feeding the same people with whom I had once crunched numbers—feeding them such things as delicately smoked trout, carefully plucked baby greens, dainty golden beets—creating small, precious flights of fancy in the center of big white plates. I was throwing out (or at least composting) anything that didn’t look perfect enough to conjure a certain kind of money from their wallets. Sometimes I wondered how far from the dens of Wall Street I had really come.

One morning the chef gave me an unusual order. Pointing out over the sloping hill of the estate at a herd of turkeys drifting and pecking through the morning, he told me that I was going to slaughter five of them for the kitchen. With this assignment came a revelation. Although I had always eaten meat, and even considered myself an adventurous meat eater—embracing the strange cuts and unusual parts found in outdoor markets and Asian butchers—I had never killed an animal with my own hands. A thin, clear piece of fishing line in my hands had always played the intermediary. But if you knew the chef I was working for, you would know that there was no going back.

I put on a clean apron and walked up a sloping hill, where they stood at the top, calm and stunning, feathers fanned out, their high-pitched gobbles echoing into the woods and over the creek. I stood paralyzed as the other cooks chased them down. There was indeed that proverbial window through which I momentarily peered and contemplated life as a vegetarian.

Girl Hunter

Girl Hunter